We completed the literature revision in previous posts, and now it's time to apply this knowledge, as I had set out to do.

Watching videos, and with the help of kinovea, an open source tool, I have analyzed the gesture that is the subject of this entry through the following subset of real climbing:

- lead style

- high level climbers

- different angles of climbing

- difficulty 8b+ to 9a

- rock and competition

- both onsight and redpoint

From these I have inferred some trends that can be of interest, although I need to make clear that this is a piece of field work and not a proper scientific study. So, the conclusions here exposed are more of a personal take on the matter.

Analysis of the pulling/lock-off gesture in Climbing

If we study in slow motion our pulling movements (specifically, our upper body; added sentence on 09/10/2012; thank you, Douglas Hunter) when we are not matching, resting, clipping, in compression moves (added sentence on 08/10/2012; thank you, Gianluca), or using tiny intermediate holds, we can divide the holds into three categories; H (the one we will Hold from), R (the one we are going to Release) and T (our Target hold). Then we can distinguish several phases.

We are going to look at each of those phases to collect some data.

AVERAGE LOCKING-OFF DURATION

Phase 1: Initial. Pulling and building Momentum with both arms

This is when we are pulling with both hands from H (the one we'll keep holding) and, R (the one we are going to release); usually more force is applied on H, especially towards the end, when we are about to release R and go for T; the legs, and really the rest of the body help to impulse in a coordinated way.

Duration: most of the time, 0,30 to 0,50 seconds.

Phase 2: Pulling/locking with one arm while releasing the other

In this phase we have already released R, for the time needed to get to T. For a brief amount of time we are applying our force with one arm, the H one,

Duration: most of the times, 0,4 to 0,5 seconds, but it can be as low as 0,2 seconds in certain movements, more often with very explosive climbers, or as high as nearly 1 second on very long reaches in not very steep routes, especially with more static climbers.

|

| Shauna Coxsey - Bouldering World Cup, 2012. Photo Heiko Wilhem. Source UKclimbing.com |

|

| Chris Sharma. Demencia Senil, 9a+. Margalef (Tarragona). Photo: Pete O'Donovan |

|

| Luis Alfonso Félix. Eros Tensa el Arco, 8b+ .Cuenca. Photo: José Yáñez. |

The best climbers devote very little to no time (0,15-0,30 seconds) to maintain the desired angle and actually lock-off. What they do is to take advantage of the previous impulse so that they can keep on flexing or extending their H arm before reaching the angle needed to grab the Target, in a way that leaves little to no room for an isometric phase. This is even more true when the holds are smaller and/or the route steeper.

|

| Helena Alemán. Spanish Climbing Championship (Gijón 2012). Photo: Darío Rodríguez. Source: top30 facebook |

Phase 3: Stabilization and getting ready for the next move

Our hands are already on the H and T holds, and we are locking-off to a certain extent (although most certainly with different angle and lower intensity) with our H arm, while we steady ourselves, do the required footwork, and adjust our fingers to the T hold so it can eventually transition into our new H hold. Next we will 'undo' the lock with our former H -and soon-to-be R- hold, and move our feet in preparation for the following move.

Duration: most often 2 to 3 seconds, going up to 5 seconds or more in the most complicated movements. This phase comes out as the longest one.

|

| Giannis Agathokleous |

|

| Sean MacColl - Bouldering World Cup - Vail, USA 2012. Photo: Heiko Wilhelm |

I have recorded 2-5 second locks when:

- trying to onsight a route, while figuring out how to grip a hold.

- in some sections that demand precision and body tension, like aiming for a pocket or climbing on roofs...

- when clipping the rope, more often in competition where clipping points are used to increase the route's difficulty.

|

| Mina Markovic. Lead Climbing World Cup, Kranj 2011. Photo: Luka Fonda |

It varies with the steepness of the route and across different moves. The most used one, though, and the most specific is the 90º one. In second place come those close to 45º, typical of slight overhangs, transitions from roof to vertical and gastons.

|

| Javipec at Bayuela |

- The more overhanging and/or tinier the holds both hand and foot ones, the shorter the locking time for a given hold separation.

- Personal style: hesitant and static; onsight (in contrast with worked), routes (compared with boulders) will yield the longest locking-off times for the same difficulty.

- Girls in general show longer times in all phases due to our lower maximum and explosive strength. If we add that training frequently ignores gender particularities, and the tendency to choose routes that keep us from challenging our weaknesses instead of working on them, there is a tendency to develop a more static style. The outcome is an increased fatigue for a given route (due to a longer time grabbing each hold), lack of ability to solve certain moves like dynos or very steep overhangs, and a general slow down of progression. Even overuse injuries in the elbows.

LOCKING-OFF AVERAGE INTENSITY

If we measure the intensity by the percentage of body weight that the arm has to bear, and look at the 2 phases where lock-off takes place, we observe the following:

- Hand releasing phase: the intensity can be high or medium depending on the type of move and overhang angle, but as far a I have been able to observe, rarely does the H arm bear a high percentage of the body weight, and, as stated above, this isometric phase tends to be lower than half a second long.

- Stabilization: Here body mass is already supported by both arms, so that intensity is even lower than in the previous phase.

INTERVAL BETWEEN LOCK-OFFS/PULLS

It is around 10-15 seconds in average. Less frequently, it lasts 5-8 seconds, or more than 20, but it is conditioned by the holds distribution, the need to clip and, as ever, the climbers' style. We need to be aware that we need to clip approximately every 2 movements in competition, or every 4 to 6 in rock climbing.

- Hand releasing phase: the intensity can be high or medium depending on the type of move and overhang angle, but as far a I have been able to observe, rarely does the H arm bear a high percentage of the body weight, and, as stated above, this isometric phase tends to be lower than half a second long.

|

| Jorg Verhoeven - Lead Climbing World Cup - Denver, 2011 |

|

| Nacho Sánchez. Tolmojón, 8B+ (Tamajón, Guadalajara). Photo: Raúl Santano. Source: flickr |

INTERVAL BETWEEN LOCK-OFFS/PULLS

It is around 10-15 seconds in average. Less frequently, it lasts 5-8 seconds, or more than 20, but it is conditioned by the holds distribution, the need to clip and, as ever, the climbers' style. We need to be aware that we need to clip approximately every 2 movements in competition, or every 4 to 6 in rock climbing.

¿Are any of these figures of relevance to medium and lower level climbers?

The numbers above are applicable to climbers with a high technical and physical level, but can vary wildly among medium and low level climbers. In fact, they do.

From my observations, the less experienced climbers display longer locking-off times, possibly due to:

- limited perceptive and motor repertory that leads to indecision when it comes to sorting out a sequence,

- reduced balance and poor management of the center of mass, that makes them try to put their body 'closer' to the holds, flexing their arms too often and locking-off constantly,

- insecurity due to their lack of experience or their undeveloped control of fear,

- insufficient memorization to climb fluidly through the key sections.

|

| Source: www.mikeoffthemapfiles.wordpress.com |

My answer is clear. It would be sensible to focus on the latter strategy during the initial and intermediate stages (2-4 years), and then to progressively include specific physical contents (like lock-offs, finger maximum strength, etc) once we are in the right path of technical-tactical improvement.

And now that we know a bit more about how long a lock-off usually lasts, in high level climbers, we can ask ourselves the question:

All right, then... ¿is it useful to train 'long' lock-offs to improve an action that normally lasts less than half a second?

My answer is Not. And, to elaborate on it, in the next entry I will talk about the importance of training for each of the phases using exercises whit specific duration, speed and intensity. I can tell you in advance that we'll learn about some explosive isometric methods and exercises, that will try to develop our ability for reaching very quickly our force peak, within those tenths of a second when we 'stop' pulling and 'lock' to make contact with our Target hold. We will also take a look at other exercises with a duration and style oriented to the previous phase, when we are pulling from the holds, something that is tightly associated with the locking-off gesture.

In conclusion:

Locking-off, at least in modern routes and competitions, and for climbers with a high technical-tactical level, is ideally a very brief action, and of medium an low intensity in general. In a way, it probably wouldn't deserve to be called lock-off...

In addition, the the time that passes between the harder pulls and lock-offs should be enough to recover from them in most occasions.

However, it is the intensity factor along with the duration, especially during phase 2, what will determine if in some instance -for a particular route or style that we are training for- this locking-off ability could become the limiting factor to send a route. This leads, you saw it coming, to another question:

What kind of movements or routes can benefit from training our locking ability?

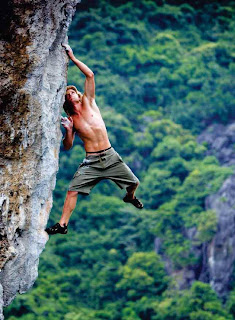

By closely looking at these pictures or thinking a bit by yourself, you may find the answer:

You got it...

For some moves in roofs, or going from a roof to vertical, crossing hands when traversing an overhang, holding a barn door, a key clipping...

For these, or other cases that you consider this ability is important for... what would be the best method to train it?

Perhaps with the information that we have to this point you can answer this question by yourself, but, if it's not the case, the next entry will be devoted to reflecting about it. We will discuss the usefulness of methods like functional isometrics, Cometti's static-dynamic pull-ups and other, less known, ones...

NEXT ENTRY: Locking-off training methodology

RELATED LINKS:

Lock-off strength training (I)

Lock-off strength training (II)

Locking-off, at least in modern routes and competitions, and for climbers with a high technical-tactical level, is ideally a very brief action, and of medium an low intensity in general. In a way, it probably wouldn't deserve to be called lock-off...

In addition, the the time that passes between the harder pulls and lock-offs should be enough to recover from them in most occasions.

However, it is the intensity factor along with the duration, especially during phase 2, what will determine if in some instance -for a particular route or style that we are training for- this locking-off ability could become the limiting factor to send a route. This leads, you saw it coming, to another question:

What kind of movements or routes can benefit from training our locking ability?

By closely looking at these pictures or thinking a bit by yourself, you may find the answer:

|

| Mina Markovic. Lead World Cup (Kranj 2011). Photo: Luka Fonda |

| ||||

Dani Andrada. Ali-Hulk, 9a+ (Rodellar, Huesca). Photo: Pete O'Donovan

|

|

| Nacho Sánchez. Insomnio, 8C (Crevillente, Alicante). Photo: Rebeca Morillo |

For some moves in roofs, or going from a roof to vertical, crossing hands when traversing an overhang, holding a barn door, a key clipping...

For these, or other cases that you consider this ability is important for... what would be the best method to train it?

Perhaps with the information that we have to this point you can answer this question by yourself, but, if it's not the case, the next entry will be devoted to reflecting about it. We will discuss the usefulness of methods like functional isometrics, Cometti's static-dynamic pull-ups and other, less known, ones...

NEXT ENTRY: Locking-off training methodology

RELATED LINKS:

Lock-off strength training (I)

Lock-off strength training (II)

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0304-5290

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0304-5290

really intreresting analysis!

ReplyDeleteas a newbie in climbing instruction i especially like the preparation/execution model and think it is a good framework to teach "good" climbing at any level.

thinking over it, howeer, i maybe found another excepion in compression bouldering, be it outdoors (fontainebleau!) or indoors (WC-like "volume hugging").

it seems to me that this situation violates some of your statements:

-relative lenght of the two phases. Most of the time the quickest solution for move preparation is the most effective (even if not always the nicest looking, nor the most energy efficient)

-straight arms. by definition made difficult because of the necessity to constantly "squeeze" the structure.

would you somewhat agree?

what % of bouldering did you include in your video analysis? was it mostly crimpy/pulling style?

a comment might make my mind clearer on this!

thanks

Gianluca

Well the subset studied include only lead climbing, so... no boulders! (specified in the first lines of the post). I guess it could be confusing because there's some pictures involving boulder, but those are only there to illustrate the explanations concerning the gesture analysis.

DeleteHi Gianluca,

DeleteThank you!

You are right, "compression moves" are another exception.

Regarding what percentage of bouldering did I include in my video analysis? as you already have seen, it only included lead climbing and pulling/lock-off gesture.

But It's true that the pictures involving boulder might be confusing. I'll think about to remove them from this entry.

Many thanks for your contribution.